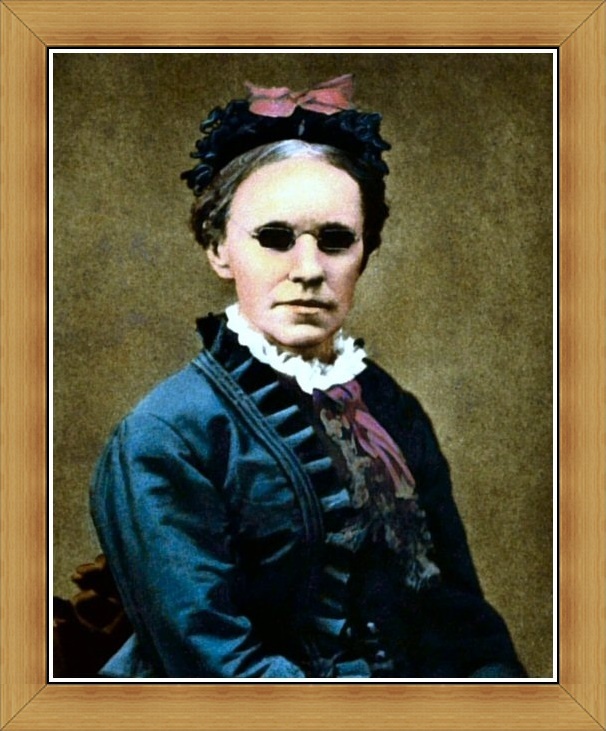

Fanny Crosby

In my book, Eternity through the Rearview Mirror, I profile seventeen historical figures. From Galileo to Johnny Cash, I let these people speak to us from their heavenly vantage point. Fanny is not in the book, but I have come to appreciate the true Christian hero that she is. Fanny was an amazing woman! So here is Fanny, speaking to us from the heavenly realm. It’s a biography that’s an autobiography! I hope you enjoy her story.

Fanny Crosby 1820-1915

“This is my story, this is my song. Praising my Savior all the day long . . .” Isn’t that a lovely way to start your own story—taking a line from the hymn “Blessed Assurance.” Oh, to write such words! Well, it turns out… It just so happens… I was the one who wrote those words!

As a child, had you ever wished for X-ray vision, like Superman’s? Most everyone would say yes! I say most everyone, because I, Fanny Crosby, never had that desire, even though I was totally blind.

It seemed intended by the blessed providence of God that I should be blind all my life; and I thanked Him for the dispensation; I was so very grateful. I assure you I meant it—every word of it; and if perfect earthly sight had been offered me, I would not have accepted it. My heart could see, dear ones; my heart could see. Sight would have been such a distraction!

On Becoming Content

As a young girl I didn’t think I was limited by my lot; indeed my blindness caused my other senses to be greatly accentuated, and because of that I enjoyed many things. A bit of a tomboy, I could never sit still, and my days would be spent climbing trees, scaling stone fences, riding bareback, playing with my little lamb, and what can I say—just finding ways to get into mischief. Winning at Blind Man’s Bluff was a breeze!

I lived many lives with my imagination. Sometimes I was a sailor, standing at the mast-head, and looking out into the storm; sometimes a general, leading armies to battle; . . . then the leader of a gigantic choir of voices, singing praises to God.

My ambition was boundless; my desires were intense to live for some great purpose in the world and to make for myself a name that should endure; but in what manner was that to be done? Me, Fanny Crosby, a poor little blind girl, without influential friends.

Gradually, however, I came to realize that I was not like other children. So many adults telling me I could not do thus and so because I was blind. That hurt, and feeling blue, I’d sneak off to be on my own. In my prayers, though, God assured me that he had great plans for me, and I came to believe him, for he always speaks the truth.

I became content with my blindness, and did not even think to pray for sight; there was a greater concern on my mind. I prayed for an education. Blind people were not teachable, it was thought, or at the very least, no one knew how to teach us.

Dear Lord, I would often pray, please show me how I can learn like other children.

On my own I began composing poetry. Have a listen to this, my very first poem. I was eight:

Oh, what a happy soul am I. Although I cannot see,

I am resolved that in this world, contented I will be.

How many blessings I enjoy that other people don’t.

To weep and sigh because I’m blind, I cannot, and I won’t.

Something I can do—and I think anyone could do if they just put their mind to it—is memorize. Before I was 10 I could recite the Bible, and whenever I wanted, I would just turn a little button in my mind and any part of it would appear, flowing through my brain like an audio recording.

In November 1834, Mother found an advertisement for the newly founded New York Institution for the Blind. O, thank God! He answered my prayer, just as I knew he could. It was the happiest day of my life.

Coming of Age

A school for the blind was quite an anomaly in the early 1800s, and we had many visitors, famous and not famous. Some would ask silly questions, like how did I ever manage to feed myself; how did I find my mouth? Oh, I would tell them, I’d tie one end of a string around a table leg and the other around my tongue and work the food up that way!

It was while a student that I had a watershed moment, calling it my “November Experience.” I was in church and we were singing. Just as we finished with, “Here, Lord, I give myself away. Tis all that I can do,” I felt my very soul flooded with celestial light. For the first time I realized that I had been trying to hold the world in one hand and the Lord in the other.

No more would I compartmentalize my actions, my thoughts. Along with that came less of a need for the worldly: I no longer felt a desire to make a name for myself, and money was less important. I laid aside my earthly ambitions for a life dedicated to God.

On Becoming a Prolific Songwriter

It was 1851 and I turned from poetry to writing lyrics for hymns—quite by happenstance. (Oh, really?) Well, I had known George Root for some ten years before I heard that lovely little tune he composed and played on the piano. “Oh, why don’t you publish that, Mr. Root,” I said. “I have no words for it,” he replied. I wrote words for his tune, and he liked them! And that was the beginning of my song-writing career.

Once I started, I couldn’t stop, writing thousands of lyrics over the years—somewhere between 8,000 and 9,000 hymns and Gospel songs. I lost count; sometimes forgetting my own lyrics. I embarrassed myself more than once, when after inquiring as to the author of such a lovely hymn only to find out the composer’s name was …Fanny Crosby! I also wrote secular poems—1,000 of them, five cantatas, two best-selling autobiographies, and co-wrote many political and patriotic songs, all supporting the North, of course, in the Civil War.

I had a certain process for writing every one of my songs. It may seem a little old-fashioned, always to begin one’s work with prayer, but I never undertook a hymn without first asking the good Lord to be my inspiration.

I wasn’t blessed with legible handwriting, to be sure (I was blind after all), so I seldom used paper and pen. Instead, I composed songs in my head—as many as forty at a stretch—waiting for someone to come along and take dictation. I had no trouble in sorting and arranging my literary and lyric wares within the apartments of my mind. I wrote and sold songs up until I died; was paid about $2 apiece for them.

A New Chapter, A New Verse

Then along about my sixtieth year, I added a new chapter in my life—one that lasted another thirty years, give or take. I became a mission worker in the Bowery. I moved to a rundown apartment—just at the edge of it. I didn’t care. I could have lived better, but I had other priorities and chose to give away most everything.

The Bowery was the New York Slums: dance halls, taverns, and small shops selling filthy pictures. Homeless Civil War veterans—usually with one or more limbs missing—roamed the streets along with prostitutes, alcoholics, and pickpockets. There, you could pay money to see a dancing bear or a man bite the head off a rat. It was the Water Street Mission, the Bowery Mission, and the Door of Hope—a home for unwed mothers—that I gave my attention to, gladly living and working among the downtrodden.

A month shy of 95, I went to heaven. Throughout my life my sight came from the heart and soul, as surely as I am here with God in heaven. One of my personal favorites from the songs I wrote begins like this: Tell me the story of Jesus; write on my heart every word. When I greet you in heaven, I’ll still be the one telling you all about him. Oh, what songs you have yet to hear!